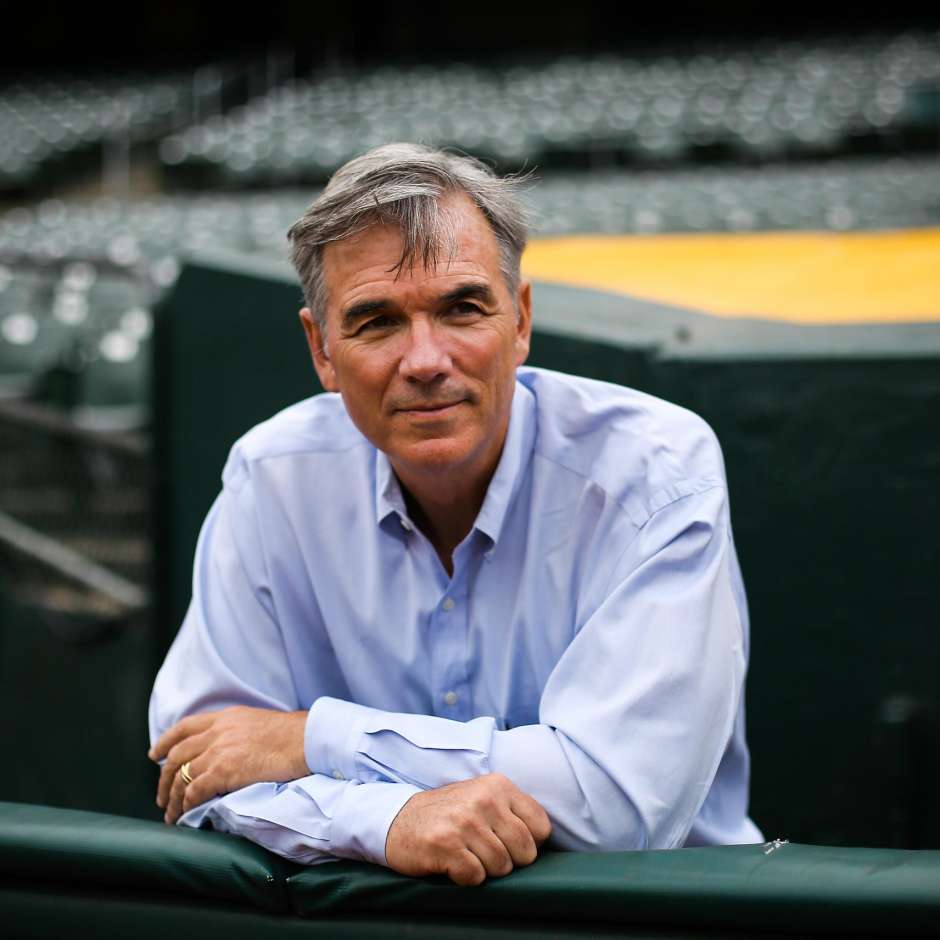

“(Signing for the NY Mets instead of going to Stanford University) is the only decision I would make in my life about money” – Billy Beane

During his sophomore and junior years of high school, Billy Beane was someone with whom you would attribute the term “baseball prodigy”. With a batting average of .501, it was nothing short of exceptional, and although it dropped to .300 in his senior year, the scouts were convinced that Beane was going to be the next biggest thing in baseball.

The New York Mets picked him up in the first round of MLB draft for what is equivalent to around $400,000 in today’s terms. The team had a lot of high hopes from Beane, but the tougher competition was too much for him. He couldn’t adjust to the higher demands of the professional game, and he retired 5 years after he was drafted.

He later took up a job as a scout for the Oakland Athletics (where he retired at) under their GM Sandy Alderson. Under their owner Walter A. Haas Jr., the A’s had the largest payroll in MLB. After Haas died, the new owners asked Alderson to slash the wage cost. To go about it while fielding a competitive roster, Alderson focused on sabermetric principles (developed and advocated by Bill James) to sign players based on metrics which were important to the game, but ones which other teams didn’t focus much on. He realised that the “on-base percentage”, in other words, the frequency of a player getting on base, was far more important than pure hitting stats, or glory plays like bunts for stealing bases. As a result of this, the Oakland A’s signed undervalued or discarded players who excelled in such metrics, and Alderson was successful in building a good enough team while significantly reducing the wage bill. He taught the same thing to Beane as well.

Billy Beane succeeded Alderson as the Oakland A’s GM on 17th October, 1997. He took the same strategy in his stride and assembled one of the most cost-effective teams in baseball. The 2002 A’s became the first team in 100+ years of American League Baseball to win 20 consecutive games. The 2006 A’s team had the 7th lowest payroll, but had the 5th best regular-season record.

A wonderful example of what the Oakland A’s did was the role conversion of Scott Hatteberg from catcher to first baseman. Hatteberg was hindered by an elbow injury, which resulted in him not being able to throw properly, and as a result his career as a catcher was effectively over. Oakland A’s saw that he had a high on-base percentage, and signed him on and re-trained him to be a first baseman. This paid off, when the A’s were on a 19-game winning streak, and in their next game with the Kansas City Royals, the A’s had blown a 11-0 lead. They were tied at 11-11, when Hatteberg came to bat. He hit a homerun and won the game for the A’s.

These tactics have been emulated in different sports, one of which is football. Usually, clubs prefer to sign players with big reputation, players who can bring both revenue into the club (through shirt sales, matchday revenue etc.) and a substantial performance improvement as well. These kinds of players cost a significant sum of money, and their contractual demands are usually not insignificant.

Even scouts and other staff focus on certain statistics or metrics which, according to them, are important, but technically they might not be. This results in clubs signing players who might look flashy on the field, but whose end product leaves something to be desired.

Brian Clough practised something similar to this when he signed Kenny Burns for Nottingham Forest. Kenny Burns was known to be bellicose and inebriate and was not wanted by most clubs, but beneath all that was a shrewd footballing brain, and a man for the big matches. He was a central defender, but Clough and his assistant Peter Taylor converted him to a striker for the 1978 season, when he became the Football Writers’ Footballer of the Year.

Nowadays, due to the advent of sports analytics agencies like Opta and Prozone Sports, utilisation of such metrics has become commonplace. Tackles per 90, goals per 90, saves held vs saves parried, xG (goals expected), etc. are few of the common metrics used nowadays to scout the right talent.

SC Caen, a small club in France, had a diminutive but industrious midfielder. In the 2015-15 season, he had fantastic scores in most of the relevant metrics for his position; 4.8 tackles per game, 2.9 interceptions per game, and 0.9 clearances per game. He was spotted by Leicester City and brought to the club in the 2015-16 season for £7.65M. He, along with Danny Drinkwater (who had signed for the club in 2012 for a small sum) became a vital midfield partnership which helped Leicester City unthinkably clinch the Premier League title in that season. In the next season, the player moved to Chelsea for £35M, netting Leicester a profit of around £27.35M. The player’s name is N’Golo Kanté. He is 5’6.5” tall, which probably was a reason for him being ignored by most clubs, who were probably of the impression that he was too short, but now he is regarded as one of the best box-to-box destructive midfielders in the game.

Liverpool FC, whose owner John W. Henry is a massive fan of Billy Beane and Bill James, also tried to do similar transfers, albeit with mixed results. The moves of Luis Suarez and Jordan Henderson were extremely successful, but the move of Andy Carroll wasn’t. This is an example of how it won’t always work in real life. Every transfer is sort of a gamble one has to take, and hope that their cards are strong enough.

The key to all this is finding the undervalued and underappreciated statistic that correlates to winning before anyone else does. That is Moneyball.

The story of Billy Beane was the inspiration behind the book “Moneyball: The Art of Winning an Unfair Game” by Michael Lewis and also the much acclaimed movie adaptation of the same name starring Brad Pitt in the role of Billy Beane.